Casting a wide net: The business of sports podcasting

- SportsPro

- Nov 13, 2020

- 12 min read

“I see this as a US$4 billion industry in two to three years, not the US$1 billion as the ‘analysts’ project.”

Kevin Jones, chief executive and founder of sports podcast network Blue Wire, might have a vested interest in projecting a bountiful future for his sector but he is not the only one betting big on a medium that has been growing rapidly over the last decade.

When Spotify acquired digital sports and culture outlet The Ringer back in February, it marked the fourth podcast company acquisition made by the audio streaming giant in the space of 12 months. That US$400 million spending splurge saw Gimlet Media, Anchor FM, and Parcast all come under the control of the Swedish company. And it is not just networks being snapped up, either. In May, the Joe Rogan Podcast, a chart leader in most English-language markets and previously withheld from Spotify by the host, was acquired by the firm on an exclusive license for a reported US$100 million.

The addition of The Ringer - which brought founder Bill Simmons’ eponymous podcast into the fold, as well as the platform’s editorial staff – cost Spotify another US$196 million and demonstrated the value of the sports element of the equation. Daniel Ek, the Spotify chief executive, said at the time that his company was “basically getting the new ESPN”.

With The Ringer, I think we bought the next ESPN, and that's going to be a tremendously valuable property. Daniel Ek, Spotify chief executive

That is a nice soundbite, especially as the current ESPN also has a fair amount of skin in the game when it comes to podcasts, sports or otherwise. In June, its podcasts were downloaded 42.7 million times, the eighth month in the last nine with a total of 40 million or more.

The US sports media giant’s streamed audio combines repackaged TV and radio shows with original content; in June, the latter saw a 65 percent increase in downloads year-over-year, totaling 17.1 million.

While those numbers are impressive, they pale in significance as a medium compared to digital video. As of 2019, YouTube had 31 million channels, while Spotify currently has around 1.5 million podcasts. In terms of sheer size, streamed audio is a small sector. So why all the fuss? Perhaps more so than video, podcasts are an incredibly effective marketing tool.

An Edison Research report in 2018 found that 90 percent of podcasts are listened to in solitude. A study by Wired in the same year found that 93 percent of listeners consume the entire episode, and Spotify’s own research in 2019 found that 81 percent of people have researched or purchased something they heard of first on a podcast. Few can expect a six-second ad insert in a YouTube video to achieve anywhere near that kind of engagement or conversion rate.

But while there is certainly a lot of potential in the market, not all podcasts will be profitable. According to Jones, Blue Wire is going to clear a seven-figure dollar sum in revenue this year, but the company’s model works on the basis that just 20 percent of its podcasts act as breadwinners. That is apparently a typical ratio amongst podcast networks.

As a sports specific podcast company, Blue Wire’s network combines a mix of influencer and athlete-fronted shows. Jones, who was previously a beat writer and has covered a number of US major league teams, hosts his own Striking Gold podcast dedicated to the San Francisco 49ers, but he admits the show sits within the 80 percent of his company’s podcasts that act as loss leaders.

“I know the conversations and content I'm creating alter the opinion of the fanbase,” he says, explaining the value of those shows. “The premise of Blue Wire is that these social-first creators are the new sports radio hosts. Yes, distribution is smaller now for these audiences. We think there is a transfer of power happening between older beat reporters and these sports influencers we're working with. Fans care more about their favorite influencer than the journalist.”

The data backs up that assertion. Studies carried out by PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) for the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) found that while podcast advertising is still trailing traditional radio advertising, the digital format is growing at an astonishing rate. According to PwC’s separate 2019 Global Entertainment and Media Outlook report, radio advertising's compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in the US is set to be just 0.7 percent until 2023, increasing from US$17.9 billion in 2019 to US$18.4 billion.

The IAB’s annual podcast studies have found that, since 2015, US ad revenues within the sector have grown from US$69 million in 2015 to US$119 million the following year, to US$220 million in 2017. In 2018, revenue hit US$479.1 million, and in 2019 revenue increased 48 percent to reach US$708.1 million. This year, Covid-19 has decelerated that growth with ad revenue expected to near US$1 billion, but even that is still a 14 percent annual increase and means that, since 2015, the sector as a whole has grown almost 1,350 percent.

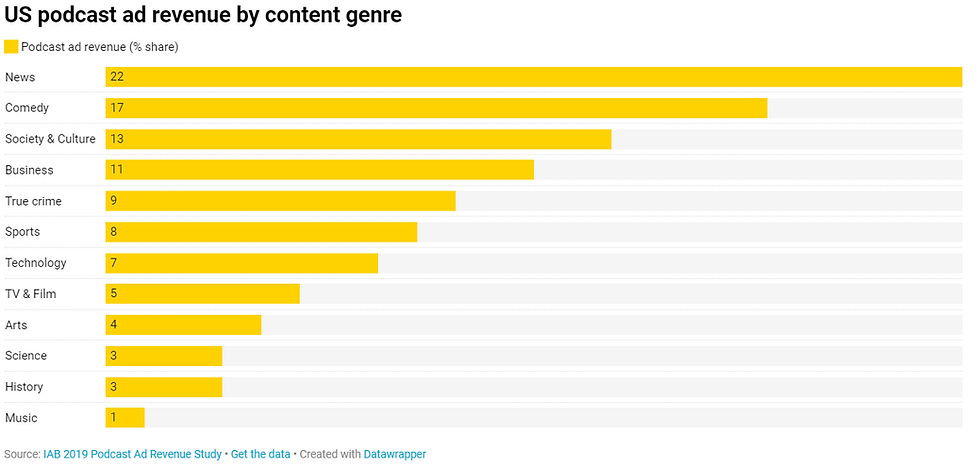

While news podcasts dominate that spend by genre, bringing in 22 percent of the entire sector’s advertising revenue in 2019, sports shows still accounted for eight percent of the pie, which amounted to around US$56.6 million last year.

In terms of making that outlay work for brands, Jones says that advertisers need to be prepared to immerse themselves in the podcast. Typically to create that sense of associated loyalty, a brand would need to purchase a package of cover artwork, a pre-roll ad, a mid-roll ad, and social posts, with contracts covering a couple of months at a time.

“We tell people dipping your toe into podcast spending, you probably won't be thrilled with the results,” he says. “It takes a plunge underwater from the brand to spend for a bigger package and then a surge of loyal listeners to start understanding that this brand is funding their favorite podcast.”

Whilst a strategic approach with the right influencer podcast series on the same network can be a “powerful audience”, it is hardly surprising that big-name athletes generate heftier buys, often in the six-figure region. Athlete-fronted shows are now commonplace among big podcast networks, with the flexibility and simple format making them attractive to the stars.

The BBC’s That Peter Crouch Podcast is perhaps the best-known example in the UK, but in the US the National Basketball Association (NBA) is a major source of athletes willing and able to front their own shows. JJ Redick, Draymond Green, and CJ McCollum are just three of the current or former All-Stars with podcasts to their name.

With their management teams behind them, those athletes are, in many cases, attempting to develop a personal brand. Few know this better than Rich Kleiman, a business partner of two-time NBA title winner and 2014 league MVP Kevin Durant. Together, the pair co-founded Thirty-Five Ventures, the investment company which manages Durant’s business interests, and recently launched a podcast network in partnership with audio production house Cadence13.

That partnership is built around The Boardroom, Thirty-Five Ventures’ media brand, which Kleiman describes as bridging the gap between the niche world of sports business and the casual fan. Initially launched alongside an ESPN+ show, The Boardroom’s main media outlet is now the eponymous podcast – hosted by Kleiman – and Durant’s own show The ETCs. However, they are both part of a broader ecosystem for The Boardroom which also features a video series, digital content, and a newsletter.

“What happened was that, as we evolved the business, I felt there was an element of the conversation that we weren’t having,” Kleiman tells SportsPro. “That’s the off-the-cuff, unpolished [conversation], wherein my opinion I’m most comfortable. So once I started exploring that it felt like that was the podcast.

“In terms of Kevin, he’s always incredible on podcasts and I felt like it was something he would want to do and pop up whenever he could. All of a sudden he expressed his interest to me to have his own platform to create.

“[The podcast] is where he could go and talk shit. Talk about all the other things in his life that he loves, moments, and time periods in his life that influenced him and be a regular person in a conversation rather than ‘Kevin Durant’. He’ll talk ball and show you that side of his mind but it felt like the right forum for that was the pod. For him, he’s very comfortable in that and it made sense.”

With a note of caution, Kleiman adds: “We have to be careful because us starting a podcast is like me saying, ‘I think I’m going to start playing ball’, and then trying to have a conversation with KD about how we both play ball. I’m not calling up Joe Rogan or Malcolm Gladwell and having a conversation like it’s one podcaster to another. We’re doing it because I’m trying to build a really big brand – well, not really big – but I’m trying to build a brand.”

I’m not calling up Joe Rogan or Malcolm Gladwell and having a conversation like it’s one podcaster to another. We’re doing it because I’m trying to build a brand. Rich Kleiman, Thirty Five Ventures co-founder

So what is the business play?

“We created these platforms,” Kleiman explains. “Now it’s my job to say to brands: ‘Listen, this is what you get from investing in the ecosystem’. There is a bit of a trust factor that we’re going to know how to spread the message through our different verticals and through Kevin’s channels. It may not look like the CPMs that your advertising teams normally use to make decisions like this; it’s not going to look the way you want yet because of the way we’re building and the fact we’re not spending massive money on media. So once I realized I had to be confident in that and who we are, the access we get, the talent we get, that is what our sell is.”

For the podcast specifically, Kleiman leans on the know-how of Cadence13, a New York-based media company that specializes in audio content distribution and monetization, but the relationship was established with the knowledge that the shows were one element of a broader strategy.

“They understand this is part of a bigger play for us,” Kleiman adds, “but it has the potential to be the biggest revenue stream of all if it works. For them, they see the value of building this Boardroom network out with us and we see them as our pod partners.”

For the likes of Blue Wire, athletes help in securing bigger brand partners. Greg Olsen, the two-time All-Pro tight end now with the National Football League’s (NFL) Seattle Seahawks, recently launched a new podcast with Jones’ company. TE1 allowed Blue Wire to do a deal with Chevrolet, a massive brand shut out of the NFL because of the league’s long-running partnership with Ford. Chevrolet uses Olsen’s podcast to market its Silverado truck as the presenting sponsor in an arrangement which includes plugs on his social media channels and ads across Blue Wire’s other shows.

Anyone who has ever listened to a podcast will have heard a read for the shaving brand Harry’s, but stars like Durant and Olsen are able to draw a different caliber of the sponsor. With big names on board, podcast networks are now looking for more high-profile partners but not always just for their deeper pockets. The likes of Harry’s have smaller marketing budgets and will base deals on successful digital conversions, whereas a company like Chevrolet has a bigger budget to make a sponsorship activation play, which is more holistically aligned and slightly less bound by analytics.

“Podcasting still is a little bit of the Wild Wild West with measurement,” says Jones when asked about the data points that matter. “It is pure downloads, really. That is what advertisers are asking for mostly at the start when they buy. But if they are looking to retain, then they are looking for some of the other data.

“The thing about pods is the number we try to flex on, [which] is people are spending hundreds of thousands of hours with Blue Wire every year. Can I say that about some sports websites? I don’t think so. So, we do need to flex the amount of time people spend with us.

“Spotify, they said openly why they made the bet. The time ratio spent with this content is absurd when you think about it compared to the other content we are bopping around on a video for five minutes, social media 30 seconds. The fact that we figured out a platform where people can consume something in 45 minutes and actually get through it is, I think, good news.”

Iain Macintosh, who founded the UK-based Muddy Knees Media (MKM) podcast network which he sold to The Athletic earlier this year, sees it similarly. He also thinks that big companies who want to invest in digital marketing see podcasts, especially sports podcasts, as a reliable format.

“One of the reasons that I felt reasonably confident about starting Muddy Knees Media was a story in I think it was The Sunday Times business section,” he tells SportsPro, “were a massive global conglomerate was cutting their online advertising by 50 percent because they said they just didn’t know where it was going - it was popping up on Al Qaeda recruitment videos on YouTube.

“Having that money come out means it is going to come back in somewhere, and a podcast audience is the best place to advertise. You know the people [and] you know what makes them tick because you know the show. You know that they are not tuning in to a station that has a slate of shows, they are tuning into that show specifically. So, it is a very good way of reaching people if you have got the scale to make it work for you.”

An advertising-based model is certainly proving effective for the likes of Blue Wire, but that 80-20 split between commercially successful podcasts and loss-leaders means it requires a lot of content to make viable at a large scale. There are, however, other ways to build a business around podcasts. The Cycling Podcast, a UK-based show dedicated to covering the sport’s elite level, blends ad revenues with a subscription model, whereby premium tier ‘friends of the podcast’ get exclusive shows and additional content.

One of the UK’s most successful soccer podcasts has taken that model to another level, with almost its entire business based on subscriptions sold to the passionate fanbase of Premier League champions, Liverpool. The Anfield Wrap launched in 2011 with close ties to a club fanzine called Well Red. A partnership with the local Radio City Talk network gave them traditional radio exposure but also allowed them to add another weekly show by repurposing the broadcast. US software firm Red Touch Media acquired a shareholding in 2013, with funds originally earmarked to back a new digital magazine, but the numbers on the podcasts convinced the founders to pursue that format, with sold-out live shows in the UK and Ireland providing further reasons to head down that path.

By March 2015, the magazine had been scrapped and the decision had been taken to launch a subscription business built around the podcasts. Initially priced at UK£5 a month, a price point which chief executive Neil Atkinson considered high at the time, paying customers gained access to two extra shows and, by the time Jurgen Klopp was appointed in October 2015, they had brought in about 1,000 subscribers.

Five years on and between 70 and 80 percent of the company’s revenue comes through the more than 10,000 subscribers who pay between UK£7 and UK£10 a month to get access to around 14 weekly podcasts and/or nine weekly videos. That is enough to support what Atkinson calls a “medium-sized business” with around 14 full-time staff.

“Our core is the subscribers and it is that subscriber income,” Atkinson says. “If the subscriber income was increasing and that [core income] changed, then we are doing something very right somewhere else and [still] something quite right on the subscriber income.

“But our focus is to get more people listening to our podcasts; as a business, that is what we want. You know, we want more people listening to our podcasts and we want more people prepared to pay for the premium shows on both audio and video.”

Like all sectors, the podcast industry is having to adapt to the realities of Covid-19 but, on a purely technical level, it is perhaps better placed to do so because of its DIY origins. All a host really needs is a laptop, an internet connection, and perhaps a half-decent microphone.

On the content side, for a short while sports shows had little to talk about but that proved to be a temporary issue. It also created content innovations that could long outlive lockdown.

At the top end of the funnel, the pandemic caused bigger issues. While certain shows saw listener numbers increase, there was an industry-wide dip as people who consumed podcasts on their way to work suddenly did not have to commute. As previously noted, the pandemic also slowed the growth of advertising revenue but Macintosh and Jones both think sports podcasts will bounce back in the long term, especially with advertising budgets likely to come under newfound pressure.

So what, then, for the future? Kleiman predicts more structure and consolidation in the space where bigger networks act like the record industry did – ironically – pre-Spotify, picking up independent podcasts with the promise of broader distribution and financial backing. To an extent, that future is already here.

For Jones, whose approach at Blue Wire is to identify and support influencers to reach engaged social audiences, the future will be dictated by what happens on the technology side.

“I think it looks completely different three to five years from now,” he says. “I think 80 percent of podcasts are absolute trash if not 90 - they are by amateurs. But podcasting, at the end of the day, is a great way to express yourself. The pressure of being on camera, that takes a lot more courage. [With] podcasting, you’re still entrepreneurial and you get to create. I don’t think that spirit is going away. I think more and more young kids will be creating podcasts than ever before.”

For the final word, though, Macintosh provides perhaps the best summation.

“When we started in 2017, we were in those final stages of having a conversation about a podcast and someone would go: ‘I am sorry, I don’t want to sound stupid, but what is a podcast?’ By 2018, that had pretty much dribbled away.

“Now, you know, that Roosevelt quote: ‘When my barber tells me to buy a stock, I know it is time to sell.’ When my barber tells me about his new podcast, that is when there might be a kind of widespread penetration. But podcasts are a thing and they are here to stay.”

Comments